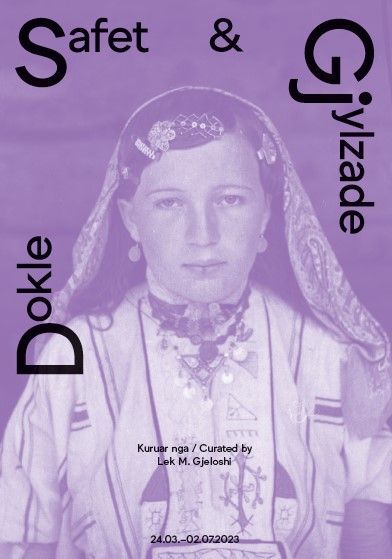

Safet & Gjylzade Dokle

–

Safet Dokle (1922-1981) was born in the village of Borje, in Kukes District. He started elementary school in Borje and then continued his studies in Durres. He graduated from Vlora Commercial Institute in 1943. In 1936, a student in Durres, he devoted himself to photography. From 1940 to 1942, to pay for his studies in Vlora, Safet worked as a photographer at school and in the city. Around 1943-1944 due to lack of electricity in his native village Borje, Dokle set up photographic printing laboratories with natural light. Safet moved to Kukes with his family in 1945, where he continued his work as a photographer. In 1946 he built a dark room laboratory to print photos at home. In 1951 he was given authorization to work as an independent photographer. During this time Safet taught photography to his wife, Gjylzade Dokle. Kosova photo studio was established in 1966 under his auspices as director of the National Enterprise in the old Kukes, with suitable spaces for photography, printing, and customer service. Safet died in 1981.

Gjylzade Dokle (1922-1996) was born in the village of Borje, in Kukes District. She completed the primary studies in her home village. In 1944 she got married to Safet Dokle who introduced her to photography and thereby became his assistant. They moved to Kukes and worked together until 1955, when she attained the necessary qualifications to work from home as a photographer for the Cooperative of Craftsmanship in Kukes. In 1966, when Kosova Photo Studio was established in old Kukes, Gjylzade worked there until her retirement in 1970. For over fifty years, she gave a precious contribution to the organization, classification and dating of negatives collection.In 1996, she moved with her family to Tirana, where she died the same year.

This photo collection depicts the political history, social life, cultural and sporting events, as well as the traditional rituals of Kukes District.

Their work has given rise to a collection of twenty-thousand negatives, including original prints and information on them.

The archive was initially turned over to the Museum of Kukes District in 1984, but after a few years, the collection was neglected and significantly damaged. Under these circumstances, Ramadan Dokle, one of the photographers’ sons, rescued much of this collection and took care of it personally, in a private space for the organization and conservation of the photographic material.

In 2021, the family decided to donate Safet and Gjylzade Dokle’s collection to the Marubi National Museum of Photography, including the equipment, thematic albums and the co-authorship – although inseparable - of the authors that represent it.

The territorial extension of this collection corresponds to the geolocation of a city: initially the old one, which was gradually submerged by the waters of the White and Black Drin river; later the new city built at the foot of Gjallica Mountain, which invites us to the underground city, fabricated during the dictatorship – and not depicted in this archive.

This three-fold existence of Kukes, same as the co-authorship of the photographers, stands in the flow between what really existed as something visible and what was renowned, but since it was not as evident as it should have been, it can only be assumed.

In this limbo, the region's strong ethnographic component is flattened. When veiled by a monochromatic celluloid, the garments and ornaments distinguished by dazzling colors, assonances and dissonances, placidly lose their vibrance in the people's bodies and in their native landscape.

In this context, as a parenthesis, a short story about a painting by Arnold Böcklin. His famous symbolist painting “The Isle of the Dead” as we know, existed in multiple versions. All versions depict a rocky islet dominated by a dense grove of tall, dark cypress “forest” and an oarsman transiting a white clad figure to the afterlife. The artist insists on using the same landscape, characters and itinerary; yet, each time, despite the differences and repetitions, it is the color variation, that distinct atmosphere which distinguish each of them. One of the versions of the series—the one from 1884—is considered lost. As a matter of coincidence, it survived only as a black-and-white photograph, obscuring the author's perseverance and the chromatic nuances, with its twilight and with its dawn.

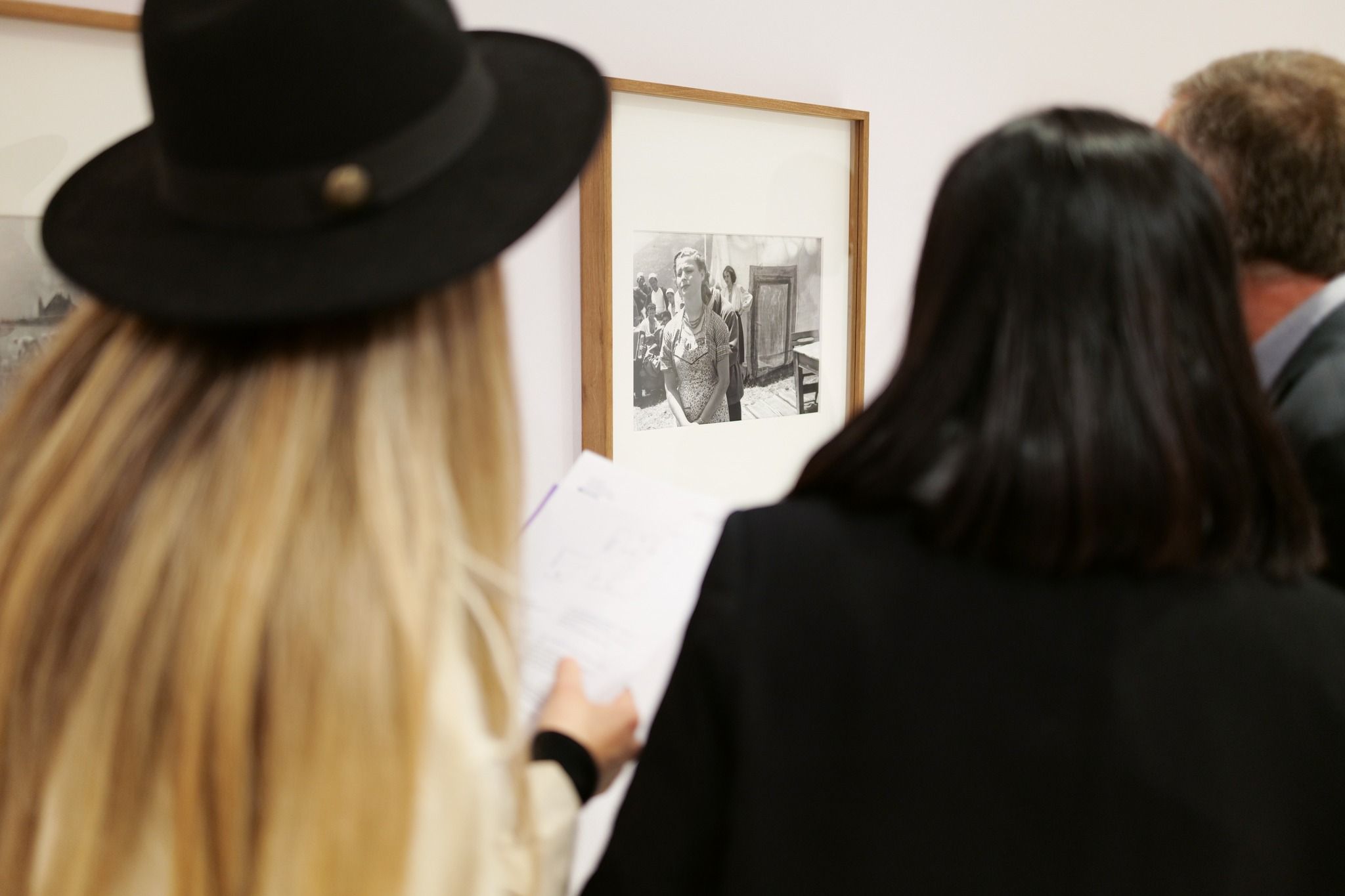

The exhibition's first section starts with four photographs. The main theme is the landscape and a perceived - or fantasized - aquatic dimension. Rather than being a painting, these tapestries become a heterotopic presence within the context of photography, where introduce another space.

In one of the photographs, a child is posing with a woman (probably his mother). There are some ambiguous details around them, as well as an accordion. A sunset, the reflection of moonlight on water, the guardrails of a balcony or terrace, and some cypress trees can be seen behind them. This subtly evokes the Isle, as well as the two subjects and that vague feeling of accompanying someone into it — probably the crying child — right after the shooting.

From this frontal pose, we move into a different direction. The focus here is on Gjylzade and the embellishments of the covers. There is no landscape here. In this area of the house, we clearly see two cushions. Maybe she is posing on a sofa or maybe on her bed; and if it were a bed, we know that this - just like the library, the museum, the cinema or the garden - is a “heterotopia”: a “counter-space” where according to Foucault, children discover the ocean, the night ghost hiding underneath the sheets, and the interruption of such fantasies when parents get back and punish their mess…

As we move on, next to the photographer’s portrait, looking her same direction, we now see a “real” landscape: old Kukes and the anguish of the city's gradual flooding which lasted nearly a decade. Even nowadays, we can occasionally notice the remains when water levels are lower.

The fourth and final photograph in this series depicts a couple posing once more, in front of a fictitious landscape, this time Venice. We can see the Saint Mark's Church Campanile, a gondoliers, and two Oriental figures conversing with locals (probably ladies or princesses).

The fact that the tapestry artwork has been associated with the nomadism of the owners as a reference to a missed or a distant place; or that the photograph with the posing couple is "hiding" – beneath the Venetian backdrop – a third one – such hints require further elaboration.

These are merely illusions in our case although they suggest a relation with backdrop, which during the earliest days of Albanian photography was related to the yard plants, before evolving into a garden painted in the studio.

In this archive we find a different virtuality, more akin to the Oriental "fantasy" than to the Western "archadia”. Most of the photographs were taken outdoors, in open areas around Kukes, with hanging tapestries or woven carpets serving as temporary (or nomadic?)backdrops. I'm referring to the impact of Oriental adventures with flying carpets and other figures suspended in the air, on the European culture of the 18th century, in addition to the scientific discoveries of the time; to the fairy tale universe of “one thousand and one nights”, whose fragrance is somehow preserved in the name of female photographer.

In another series displayed along the exhibition wall, the landscape views disappear. This series begins with a crowded 1st of May parade in old Kukes showcasing work tools. Once again, carpets and tapestries serve as a backdrop for the podiums where politicians are positioned. Instead of referencing a specific image, they create a décor, an encrypted representation of geometric and floral shapes, away from the "heterotopia" of another space.

In this horizontal series, photography becomes a frame, and its kinetics gradually "dissolves" the information. Only one of the images stops the crowds, takes a close-up and adheres to the vertical structure of the frame: it is the moment when the artisan of Bicaj, Kukes weave a unique tapestry.

The manufacture of this immensely popular handicraft all over the region required three work shifts, weaving carpets and tapestries which proved to be a huge success in international fairs. But let’s get back to the photo. Despite the ornaments, we can clearly see that it is dedicated to someone: “to comrade Enver Hoxha”.

A similar one was attempted in Shkoder for Enver Hoxha, but it never saw the light of day. This is because Shkoder artisans were terrified to weave accurately the dictator's portrait.

The artisans of Bicaj opted for different approach despite the fact that abstragation and decoration did not prevent it from bearing his portrait, revealing important personal details such as the name, the co-authors and the date 16.X.1963 - which also happens the day the work was completed and the dictator’s birthday.

One year before, in 1962, the publication of the Ethnographic Atlas had become part of the Albanian ethnographic discourse. This was mentioned by Rrok Zojzi in the periodical Albanian Ethnography. In a subsequent study entitled Ethnography in Dictatorship, it is stated that the political upheavals of the 1960s forced ethnographers to criticize and eradicate all archaic traditions — more accurately, "backwardness" — in Albanian culture. And they committed, in a programmatic way, to making contributions of this nature. The interruption of dialogue with the archaic and the past gave absolute precedence to the study of Socialist reality, whose paradigm became agricultural cooperatives.

As a result, the Albanian society accepted Soviet inspirations and the schism, embraced the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and among other things, believed in atheism.

The repertoire's final section suggests certain traces that venture beyond the broad orientations. Photography's unrestrained power of "visual unconsciousness" immortalized them. Here, we can smell the remains of the ashes of a pagan atmosphere, that feeds the image with a spiritual and mysterious dimension. Here, a bonfire burns in the dark. We see one after the other, symbols and garments, asymmetrical hieroglyphs of the embroideries, as well as the "fluffy cone" of the duvak veil with glittering sequins that recompose the figure of the horse and the anonymous bride into the magical and unique semblance of a unicorn (a mythological creature which keeps “wandering" in many tapestries since the Middle Ages).

Exhibition Credits

- Curated by

Lek M. Gjeloshi

- Supported by

Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Albania

- Acknowledgements

Familja Dokle

- An exhibition by

Marubi National Museum of Photography