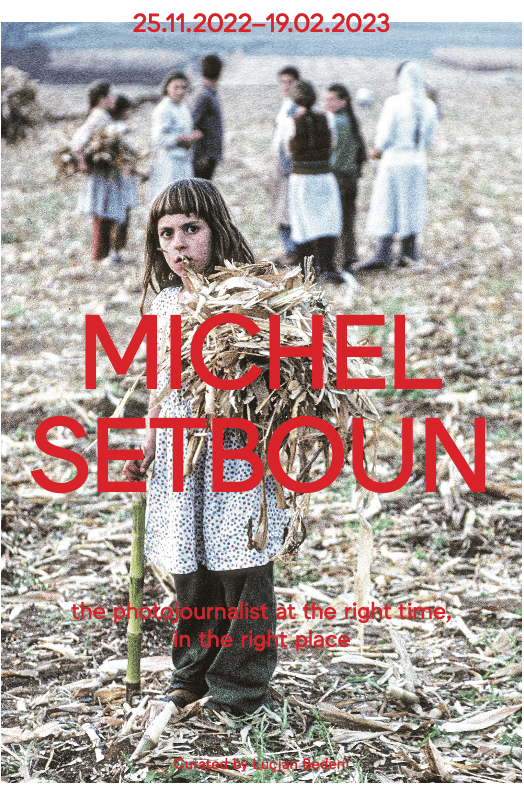

Michel Setboun

The photojournalist at the right time, in the right place

–

In November 1944 communists guided by Enver Hoxha seized power by force in Albania. An authoritarian regime was built with Marxist and Leninist ideology, similar to the other countries of the Eastern Bloc. Albania's communism was marked by pivotal events that changed the country’s political scene several times. First, the relations with Yugoslavia (1944–1948) caused political and economic havoc. After joining the Eastern Bloc (1949–1960), Albania adopted the Soviet model until this friendship was broken on the pretext of the seemingly liberal Khrushchev’s policies. The Chinese Cultural and Ideological Revolution of Mao Zedong, which Hoxha applied in Albania, became a defining feature of the alliance with the People’s Republic of China (1961–1978). After a protracted campaign to destroy places of worship and sentence clerics to death and imprisonment, Albania was officially recognized as the only atheist country in the world in 1967. In a time when the 1960s and 1970s were seen as catalysts for the post-war economic reforms marked by the fight for women's rights, anti-war demonstrations, environmentalism, sexual revolution and civil rights, Albanians were going through the worst period of terror. The 11th National Song Festival (1972) prompted the Fifth Plenum of the Central Committee of the Albanian Communist Party (1973) to condemn artists and intellectuals with incarceration and hard labor for their foreign influences and liberal attitudes, which were at odds with the socialist realism ideology and aesthetic. Albania became a totally isolated country. Only high-ranking members of the regime and a small number of participants in sports and educational activities were allowed to travel abroad. For 45 years, Albanians who attempted to flee the country ran the serious risk of being shot in border or arrested and charged with treason against the state, while the families of those who managed to flee were sent to internment camps. The final years of the dictatorship were marked by self-isolation and severe economic decline during a time when Albania had no allies among the communist countries. Enver Hoxha died in 1985. Ramiz Alia, a former political bureau member ruled the country with the dictator's widow until the fall of communism in 1991.

Photos that depicted Albanians' daily struggle with poverty were uncommon to come by. This is no coincidence because the State Security, the body regarded as the ‘dictator's eye’ was in charge of all information sources, including the photo studios which were nationalized and turned into departments of photographic service. The Albanian Telegraphic Agency—a sort of ‘shaping-laboratory of the New Man’—had control over all photographs that appeared in magazines and newspapers. Foreign tourists were subject to such control because their movements were monitored in order to prevent them from photographing the reality. During the years of dictatorship, only political delegations from friendly communist countries, athletes competing in international competitions, and tourists who met the requirements of Albtourism, the only State agency for tourism, were permitted to visit Albania.

Michel Setboun was only 17 when he started travelling the world. On one of his journeys, he stopped in Yugoslavia and in Kosovo. This moment piqued his interest in visiting the isolated Albania. Setboun arrived in Albania for the first time in 1981 disguising himself as a member of a young French Marxist group travelling there as part of a friendship agreement between the two countries.

This may be seen in his series ‘Albania 1981’ in which there are no pictures depicting the realities of jails, internment camps, the destruction of places of worship, or even poverty. ‘Life on the Streets During the Communist Regime’ is the only secretly taken photograph that captures the shock Albanians felt upon seeing foreigners. It is odd that, aside from this photograph, throughout the entire series Michel is not identified as the photographer. What we observe is an elaborate system of fabrications created by the regime to present Albania as a happy and prosperous country. Aware of the presence of a parallel reality, he returns in 1986 and every year up to communism's downfall in 1991. His trips to Albania are documented in the series ‘Timeless Albania’ and ‘The fall of communism’. His return in 1990 was different from the times he came disguised as a tourist in an isolated country. This time, he is a photojournalist in action, covering the fall of the communist system for international news agencies. If we google his name, we can understand his significance as a photographer by looking at photos of the massive Albanian escape to Europe on July 2, 1990, which can be found in the series ‘Exodus’, the first pluralist elections in the series ‘The Beginning of Democracy’ and the events following the Anticommunist Demonstration on April 2, 1991 in Shkoder in the series ‘Riots and funerals of April 1991’. Shkodra, the epicenter of communist persecution and the city of the first democratic uprisings in the 1900s, occupies a special place in his photographs. In contrast to other series with a political focus, Michel is also interested to religion. He keeps an attentive eye on the documentation of the revival of religious practices in the ‘Rebirth of Christianism and Islam’ series. Dom Simon Jubani, a Catholic priest who spent 26 years in prison and organized the first mass which heralded the fall of the dictatorship, is a central figure in these events. This exhibition focuses on Setboun's involvement in recording Albania's communist regime downfall and some rituals he captured during the 1990s; it does not include his subsequent trips to Albania.

Michel Setboun is an internationally renowned photojournalist for SIPA agency who photographed ‘The Independence War in Angola' (1976), ' The Civil War in Lebanon’ (1976), ‘The Civil War in El Salvador' (1979) where he got wounded, 'The Soviet-Afghan War’ (1979), ‘The Islamic Revolution in Iran’ (1979), ‘The Iran-Iraq War' (1983), 'Nigeria refugee crisis’ (1982) which earned him the World Press Photo first prize and the ‘September 11 Attacks’ (2001).

Exhibition Credits

- Curated by

Luçjan Bedeni

- An exhibition by

Marubi National Museum of Photography

- Supported by

Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Albania

- Acknowledgements

Pierre Raynaud

Kastriot Dervishi

Eleana Ziakou