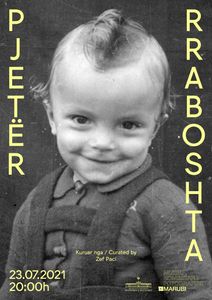

Pjetër Rraboshta

–

Pjetër Rraboshta was born in Shkodër in 1917 to an artisan father who made traditional clothing. He studied at the Jesuit-run Saverian College. He spent his early years as an apprentice at Kel Marubi’s photography studio. He completed his military service in Gjirokaster, where he practiced photography. He then returned to Shkodër, and until the 1940s, he continued to work at the Marubi studio together with Kel's son, Gegë. Around 1942-1943, he opened his own studio, "Foto Rraboshta", on the main street of the city.

By the time he started working as a photographer, Shkodër had already undergone a period of fascination with the images captured by Pietro Marubbi; then it had seen Kel's epic snapshots of well-known individuals as well as Idromeno’s unusual snapshots of ordinary people; later still it had come to know the lifestyle of a genteel and decadent stratum of society through the images of Gegë Marubi and Dedë Jakova. Rraboshta’s photographs, on the other hand, recorded an era of rapid changes, when political goals (both promulgated and concealed) were set and gradually left their traces on society.

The city he photographed was not chaotic, but it was nonetheless diverse, with a mixture of social strata and an influx of various societal changes – although the upper class appears to be missing. The images convey the atmosphere of an intimate Mediterranean city that evokes nostalgic visions and experiences.

Rraboshta's gift is his ability to present reality as it is. His subjects exude the essence of an authentic and therefore problematic lifestyle. The sense of optimism that was officially trumpeted by the regime is nowhere to be found in his photos. The happiness that he conveys is not of that kind – it is the eternal happiness of humanity that exists side-by-side with sadness, grief, and effusion.

In his photographs, there is a seeming anonymity and simplicity. Nothing is staged; rather, he captures solemn, painful, and amusing moments from the life that flows before his eyes. He simply stands in wait, not only for what is expected to occur, but also for what happens to occur, sometimes on its own and other times with the impetus of the camera’s gaze. In the typical typologies of the medium, life that has stopped, appears unruly and, sometimes, is caught in the fly in its whirlpool.

At that time, photographers were the ones who made families’ photo albums. It was up to them to go where people were located, be it in their backyards, inside their homes, at work, at holiday festivities, or on vacation. The people in these photographs appear with the appropriate stances and attire in the same angles, by a door, in front of a wall, at home, in a yard, in a church, in front of barracks, in a square, on the street, in the gardens, in the snow, or on the beach. Precisely during this repetition, it happened the unrepeatable that time and subjects brought about. The stories he presents to us are minor ones that come from the grassroots. He is not divorced from them; on the contrary, it feels as if he is part of them.

A photographic service of this kind somehow saved him from being corrupted by ideology. When lacking political and socio-cultural agendas (which were well defined by the regime), an image is more declarative and accusatory than it is explanatory. Rraboshta worked in an environment where mental and visual awareness were being questioned, yet just so, on the brink, by photographing, he seems to have preserved some of the values of the life and rites of that time and place – especially those that the regime had begun to suppress. His testimony, based on the traditional genres of photography, makes one feel the moral responsibility and dignity of a community that, in the face of an increasingly threatening and oppressive state-sponsored atheism, persists in continuing the public celebration of religious rites. His images constitute the last glimpses of these rites before they were strictly forbidden in 1967.

Fellow citizens called him “Rraboshta of the children”. This theme, at times religious in nature while at others profane, pervades Rraboshta's photographic oeuvre. It conveys moments of happiness and discomfort from both everyday life and traditional rituals, of which confirmations in particular stand out. However, his archive also extensively includes other age groups and a variety of themes reflecting on society and life with its rhythms and rites. Among the latter group, there are many images of weddings that follow the same itinerary: house, car, church, and then house again. These scenes of weddings and confirmations show a mixture of people in both ceremonial attire and everyday clothes, as both participants and spectators. In his photographs, at times, the spectators of the ceremonies become the protagonists. In a considerable number of photographs we find the presence of the theme of military service. Although the photos may have been taken during leisure time, in front of the military garrison, the subjects in uniform exude discipline through their poses.

He worked extensively throughout the mountains of Northern Albania, where his primary focus was taking ID photos. The portraits of the subjects interlock the urgency of a kind of an inner self-declaration at the edge of a single image. The subjects all came obediently (on official orders, since the government was conducting a census) to the place where the photographs were taken, each one of them posing in front of a door or some fabric. As if frozen in time, these individuals continue to look out at us to this day, staring directly into our eyes. Even though they are no longer present, we still feel the mutual gaze between the subject and the photographer, with all his emotional commitment and empathy. Among these photographs, there is also a portrait of the photographer himself.

Around 1963, following the closing of private enterprises, he joined the department of state photographers at the State Artisanal Cooperative. Rraboshta, who had traveled ceaselessly through the cities and highlands, did not go out into the field during his last years of employment in this department. Due to health issues that prevented him from going on long walks, he worked in a laboratory where he developed films and photographs of his colleagues until the day of his retirement. He had a reputation as the master of the darkroom.

In 1970, he handed his photographic archive of 16,196 images shot in film (24 x 36 mm and 24 x 24 mm) over to the state. This archive, unaccompanied by the relevant captions, relies solely on the incomparable power of its images.

He died in Shkoder in 1987.

Exhibition Credits

- Curated by

Zef Paci

- Supported by

Ministry of Culture of Albania

- Acknowledgments

Family of the photographer Pjetër Rraboshta

Muhamet Boriçi