Dedë Jakova

–

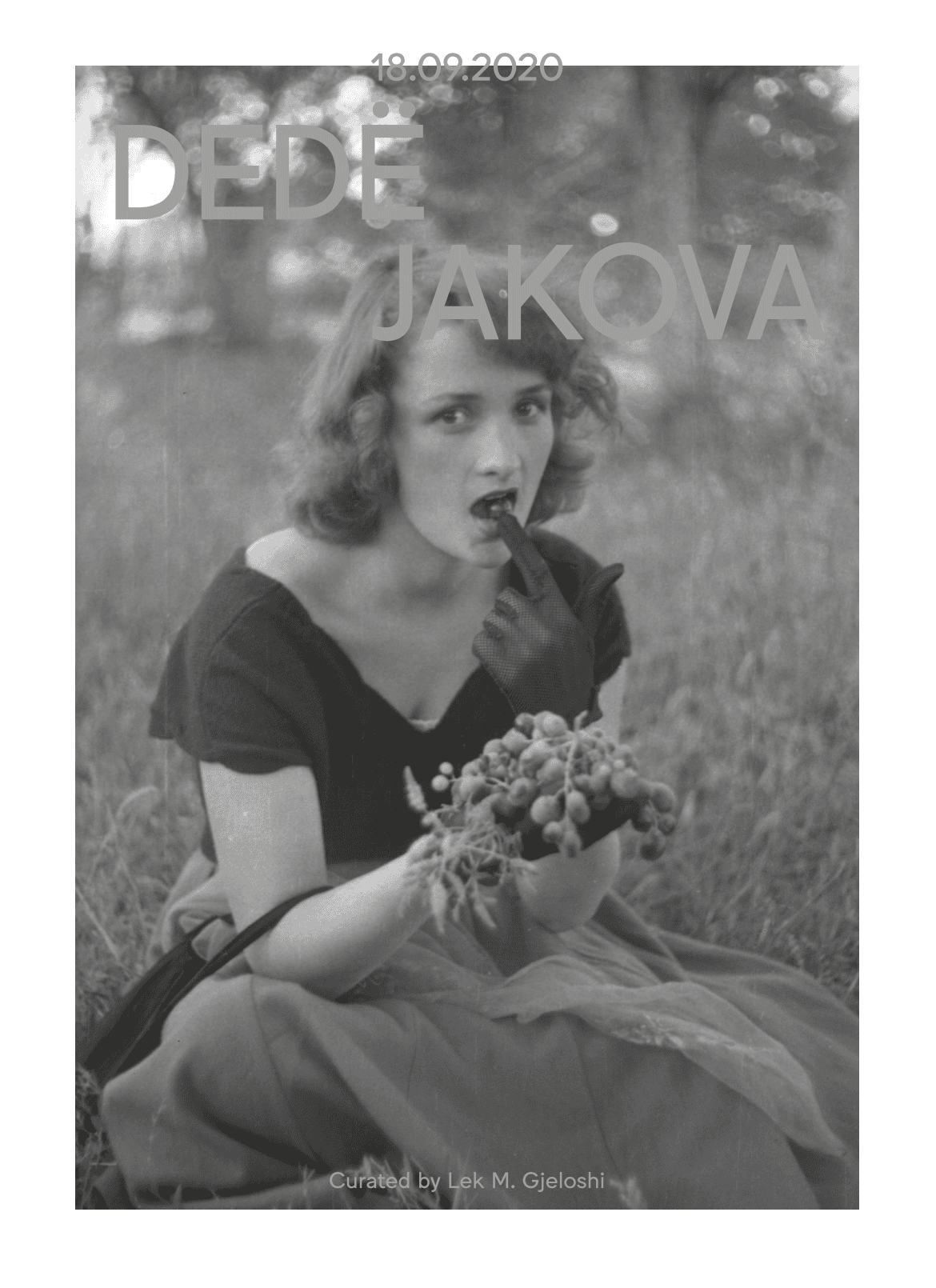

Dedë Jakova (1914-1973) was born in Shkodra, in an intellectual family. He took his first studies at the Saverian College and learned the mastery of photography from Kel Marubi. In 1932 he opened his own studio “Foto Jakova”. By the mid 1930s he was national representative with exclusivity rights for Ferrania and Lomberg Films. He made various postcards of the time and was the first photographer to accompany mountain climbers at the highest Albanian peaks. His photographs, mostly taken in Shkodra, are permeated by a strong ideological and political rotation: from images of the monarchy to the influence of fascism and the consolidation of the communist regime.

The process of nationalization initialized by the State culminated in the mid-1960s with the closing of private photography studios. Evidence from the time confirm that due to the strong pressure from the tax system, he was the last author to become part of the Cooperative of Services. In 1970 Jakova joined the other photographers who donated their collection to the State. He left a legacy of 58.000 negatives, in glass plates, roll and sheet films.

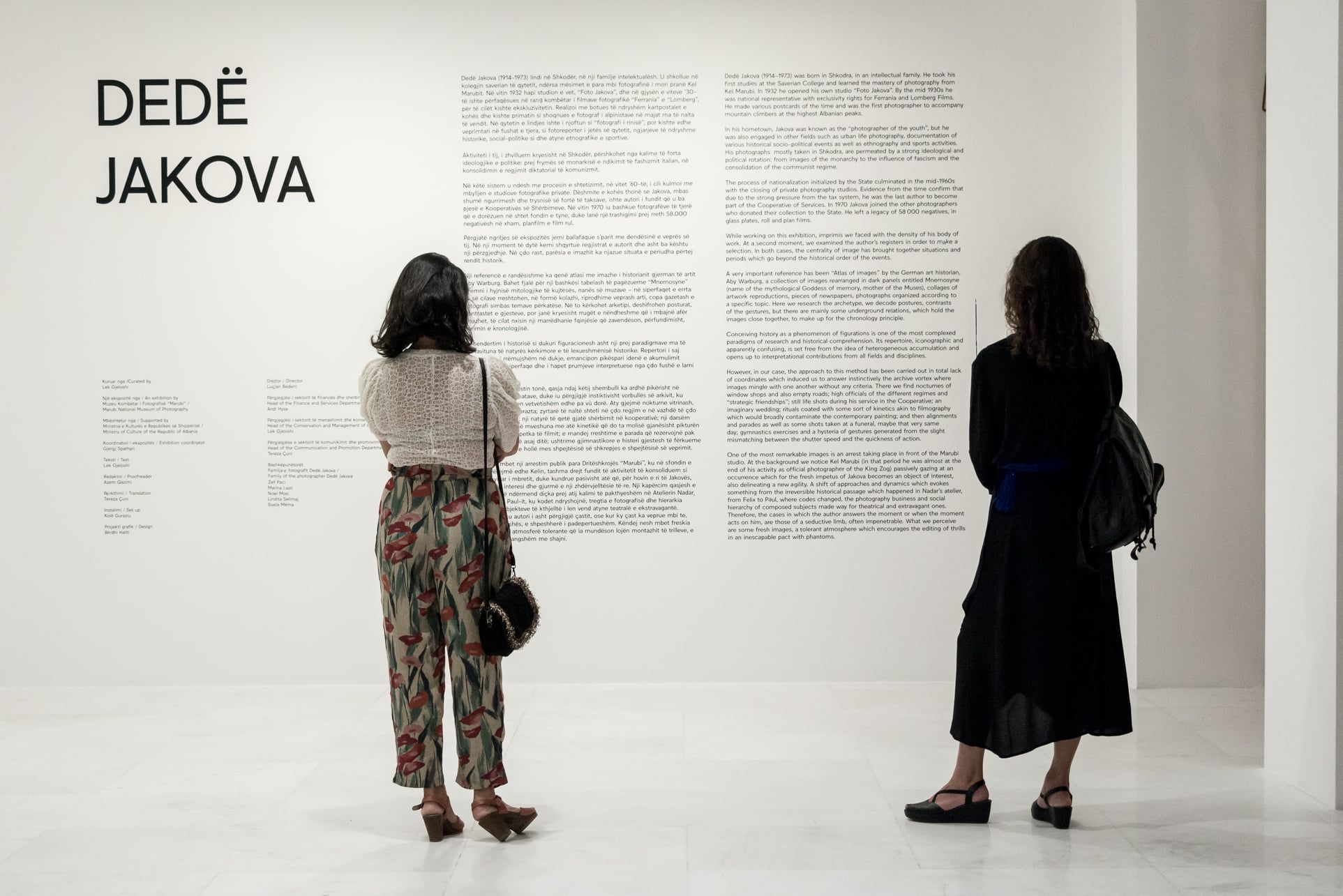

While working on this exhibition, imprimis we faced with the density of his body of work. At a second moment, we examined the author’s registers in order to make a selection. In both cases, the centrality of image has brought together situations and periods which go beyond the historical order of the events. A very important reference has been “Atlas of images” by the German art historian, Aby Warburg, a collection of images rearranged in dark panels entitled Mnemosyne (name of the mythological Goddess of memory, mother of the Muses), collages of artwork reproductions, pieces of newspapers, photographs organized according to a specific topic. Here we research the archetype, we decode postures, contrasts of the gestures, but there are mainly some underground relations, which hold the images close together, to make up for the chronology principle.

Conceiving history as a phenomenon of figurations is one of the most complexed paradigms of research and historical comprehension. Its repertoire, iconographic and apparently confusing, is set free from the idea of heterogeneous accumulation and opens up to interpretational contributions from all fields and disciplines.

However, in our case, the approach to this method has been carried out in total lack of coordinates which induced us to answer instinctively the archive vortex where images mingle with one another without any criteria. There we find nocturnes of window shops and also empty roads; high officials of the different regimes and “strategic friendships”; still life shots during his service in the Cooperative; an imaginary wedding; rituals coated with some sort of kinetics akin to filmography which would broadly contaminate the contemporary painting; and then alignments and parades as well as some shots taken at a funeral, maybe that very same day; gymnastics exercises and a hysteria of gestures generated from the slight mismatching between the shutter speed and the quickness of action.

One of the most remarkable images is an arrest taking place in front of the Marubi studio. At the background we notice Kel Marubi (in that period he was almost at the end of his activity as official photographer of the King Zog) passively gazing at an occurrence which for the fresh impetus of Jakova becomes an object of interest, also delineating a new agility. A shift of approaches and dynamics which evokes something from the irreversible historical passage which happened in Nadar’s atelier, from Félix to Paul, where codes changed, the photography business and social hierarchy of composed subjects made way for theatrical and extravagant ones.

Therefore, the cases in which the author answers the moment or when the moment acts on him, are those of a seductive limb, often impenetrable. What we perceive are some fresh images, a tolerant atmosphere which encourages the editing of thrills in an inescapable pact with phantoms.

Another important discovery of our research was Jakova himself. Besides his activity as photo reporter of different events, he seems to be at a great ease even as a subject; an extraordinary inclination to performance which shifts suddenly and without vanity to the interiority of the image. We notice this kind of inclination even in the photographs of other authors from the archive, but in Jakova’s case, improvisation occurs outside the studio, in a direct contact with people or encountered situations. This conscious predisposition would distinguish him from the traditional mentality of the photographer in the context where he worked. From that context, Jakova is named ‘photographer of the youth’. Something from the popular perception might be related to his young age, to the young age of his subjects, to their civil status. Engaged and married couples and group portraits in the studio overpass 20.000 negatives. But this genre in its complexity generates an altar of dramas of the human condition. Them staring to the left and to the right, brightened up by studio lightning, never show us the contemplated mirage which is always left out of the frame.

The archive has suggested various paths to treat this aspect without neglecting the impudent and hedonistic dimension wrapped around the word “youth”. It is precisely in this multitude of situations he has provoked – photographers are often well-known (Gegë Marubi most of all) and sometimes unknown (maybe friends) – that we might allude that each time, they answer a specific request from Jakova. His exigency to perform culminates in a photograph where he improvises, with a smile in his face, wearing a crown of flowers. What at first sight seems to be a funny pose, actually reminds us of an analogy with Dionysus physiognomy - the rebel and sarcastic God of the Greek mythology. This reference is not to be underestimated as it was not so unusual nor casual for the author. A few meters from his studio stands Kafja e Madhe (The Grand Caffe), at the time a spot of bursting city life, photographed and also frequented by Jakova. On the entrance door of the building, as a welcoming symbol, we still notice nowadays, the bas-relief of the mythological creature.

From a different perspective and language as well, it has been mainly Caravaggio’s painting to define globally this mythical figuration. There the subject, also known as Bacchus, is portrayed with a flower crown, but his posture is reclined. In his hangover look, holding a carafe of wine, we cannot read any exuberance. It seems that we arrive there after the feast. But in Jakova’s case as well as in the photograph, that Dionysian feast is the moment when the photograph is taken. To this moment, is entrusted his chuckle – magically revealed through a light and teasing transgression towards the whole happening. Thus even towards the myth of photography where the lost Real pretends to become again possible.

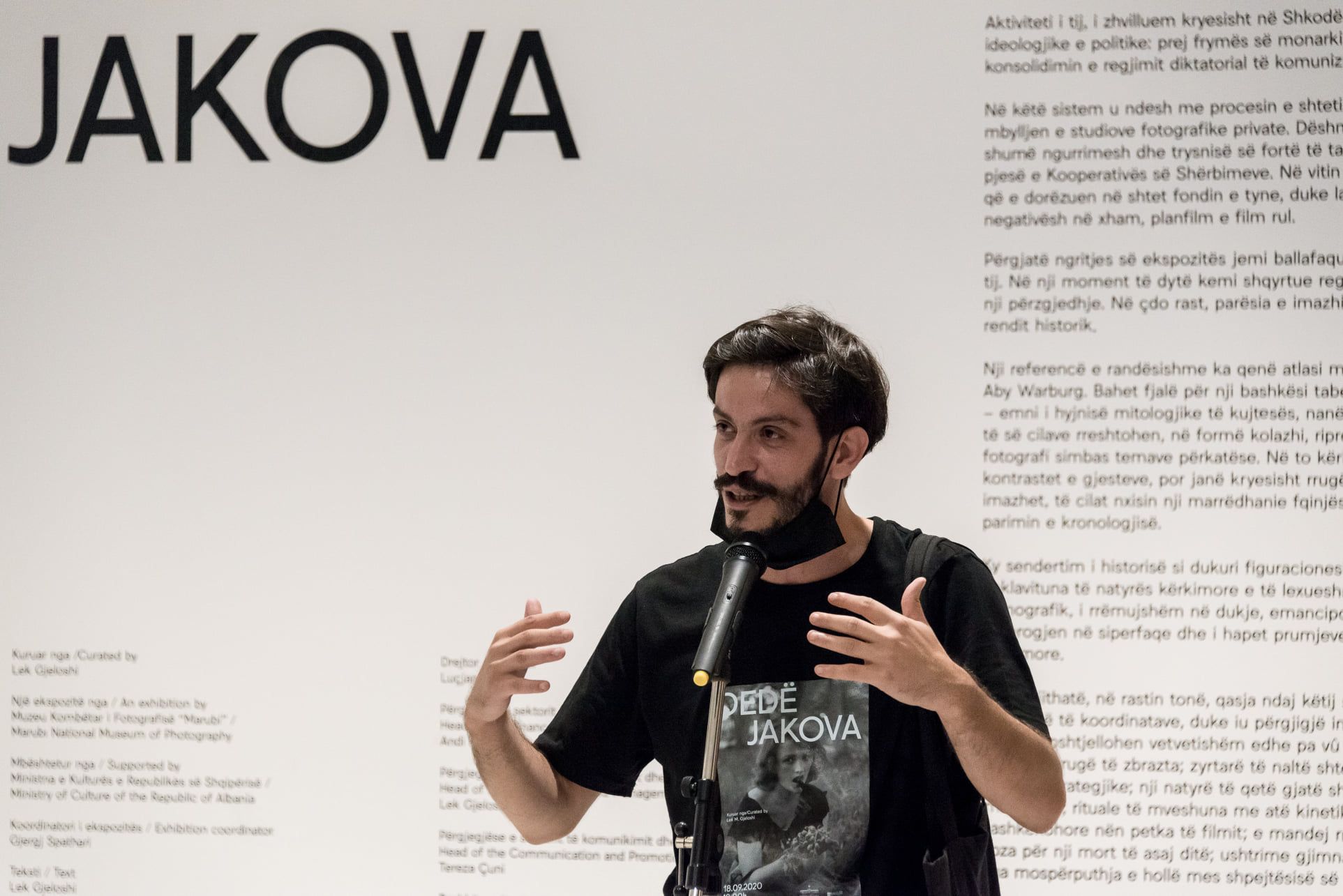

Exhibition Credits

- Curated by

Lek Gjeloshi

- Supported by

Ministry of Culture of Albania

- Acknowledgements

Family of photographer Dedë Jakova

Zef Paci