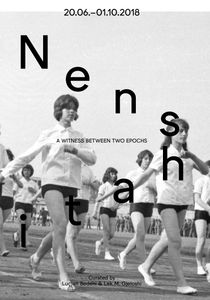

Angjelin Nenshati

A Witness Between Two Epochs

–

Artistic creativity in Albania, like in other countries of the Eastern Communist bloc, followed the ideological stream of socialist realism, treated as the only worthy ideology by the communist regime in regards to the fields of literature and the arts in general. The “red star” was the spirit of the communist ideology during this time and it pervaded as the aesthetic form, which turned it into an instrument used to propagate the revolutionary ideals of the communists and their optimism for the world they wanted to create. All of this was accomplished through artistic work presenting an ideological transformation of reality. By following the political route, of an only existing party, the idea of the “new man” was presented as the fruit of revolutionary victories, a winner of battles for the transformation of the world. This ideological person did not represent a contradictory reality, or the individualism of a human being, nor did this person possess any kind of naturalness.

“We're dealing with a kind of prototype shaping lab” — as defined by researcher Gëzim Qendro — which goes beyond the will to display the model of the new man in every artistic and cultural aspect by “conspicuously hiding him from photography, cinematography, painting, sculpture, everything.”

The exhibition dedicated to Angjelin Nenshati, the photographer of the country’s historical transformations, is divided into two parts: the period during the communist dictatorship and the transitional period of the 90s.

If the 1960s, years of the fraternal friendship with the Soviet Union, presented to us the triumphant spirit of the regime at that time, according to cliché “man and war”, the 1970s – photos from this decade are mostly prevalent in this exhibition – focused on the theme “man and work” and the experiment of the Chinese cultural revolution in the Albanian society.

These decades are characterized by two important moments of ideological pressure. On the one hand there is a struggle against religious beliefs and customs which- with the 1976 Constitution- would lead to Albania becoming the first atheist country in the world. This tragic aspect of the cultural revolution transformed places of worship into propaganda sites of Communist ideologies. Some of these were converted into sports arenas, cinemas, cultural establishments, warehouses while others were completely destroyed. These actions ended the cleric persecution campaign that began in 1944.

Enver Hoxha's dictatorial regime, after the 1970s, was characterized by the loyal pursuit of communist ideologies, interpreted in a strict anti-revisionist view. Plenium IV (1973) was also the climactic moment of aggressive politics toward art. The main examples of this war were the cultural attack against the artists of the “Pranvera" exhibition (1972) and the 11th Festival of Song on Radio Television (1972).

In regards to these changes, the Angjelin Nenshati exhibition is built in chronological order and is oriented by three main images. In the first image appears a gymnast caught in the rings set on the altar of a church that was changed into a youth center (1967). In contrast to this, 24 years later, the photographer documents the act of “recapturing” the Cathedral where the icon of Our Lady of Shkodra- although in the second plan- stands on the stairs of the tribune of the Palace of Sports while people are getting rid of the basketball backboard (1991). In addition to documenting the reopening of religious institutions, a few days later, the photographer shows the burning of the Party’s Committee building on the 2nd of April 1991. This is considered the final event that ended the dictatorship in Albania.

In both these periods, at the heart of Nenshati’s photography, remain the events he follows with interest and with the eye of a reckless and attentive reporter. He never wants to give an author-like assessment of the events, whether they are moments of youthful manifestations, voluntary actions, propaganda of the time, or simply moments of daily life.

This disciplined position in the relationship with the present moment is also recognized in the country's major political changes of the 90s, where the above mentioned socio-political reversals completely transform the increasingly dramatic nature of the event that is liberated from the reenactment.

Exhibition Credits

- Curated by

Luçjan Bedeni

Lek M. Gjeloshi - Acknowledgements

Angjelin Nenshati family

- Acknowledgements

Angjelin Nenshati family