Lala Meredith-Vula

Wisdom today and forever

–

We find the words which give character to Lala Meredith-Vula’s exhibition at the Marubi National Museum of Photography in Shkodër on a banner, in a photograph, that the Albanian-English artist made in Vranjevc, Prishtina on 4th May 1990. They are a declaration of a principle to guide a delicate historic transformation within a community. They also seem to apply to Meredith-Vula’s entire artistic practice – at once immediate and enduring, attuned to patient processes that require social grace and a collaboration with the land including the natural materials at hand.

Some background: In August 1988, four days after installing the now seminal Freeze exhibition with fellow Goldsmith’s students, Lala Meredith-Vula left London for the Albanian countryside, where she began to photograph haystacks. Asked, “Why haystacks?” she told me that in these agrarian forms she had found “the quintessential artwork.” And if she also wished to reconnect with her homelands, such an abstract desire needed to be grounded in something down to earth, like stacking hay.

Close to three decades and hundreds of photographs later, the project has not ceased. The haystacks continue to be built by farmers from places such as Pejë, Carralevë, and Duhlë, though today less frequently. Meredith-Vula continues to index their persistent presence and what might best be called their particular personalities. Her haystacks are significantly more varied than the regular, picturesque mounds painted by Jean-François Millet or Claude Monet in the nineteenth century. Photography individuates haystacks; it turns them into contemporary, documentable, subjects.

Much has happened in these troubled regions where Meredith-Vula finds haystacks, in the intervening years. The Republic of Kosovo declared independence from Serbia, which itself was part of Yugoslavia when the series began. Even if haystacks can be photographed like you or me, and thereby gain an almost animist quality, they do not carry passports or national allegiances. Their forms are governed by habits of working the land, which are older than nations. The needs of animals and the poetic license of farmers play their parts. Yet, if haystacks do not belong in the *polis*, are not political subjects *per se*, they do bear silent witness to history; and certainly, they have brought the photographer who travelled to depict them closer to historic events.

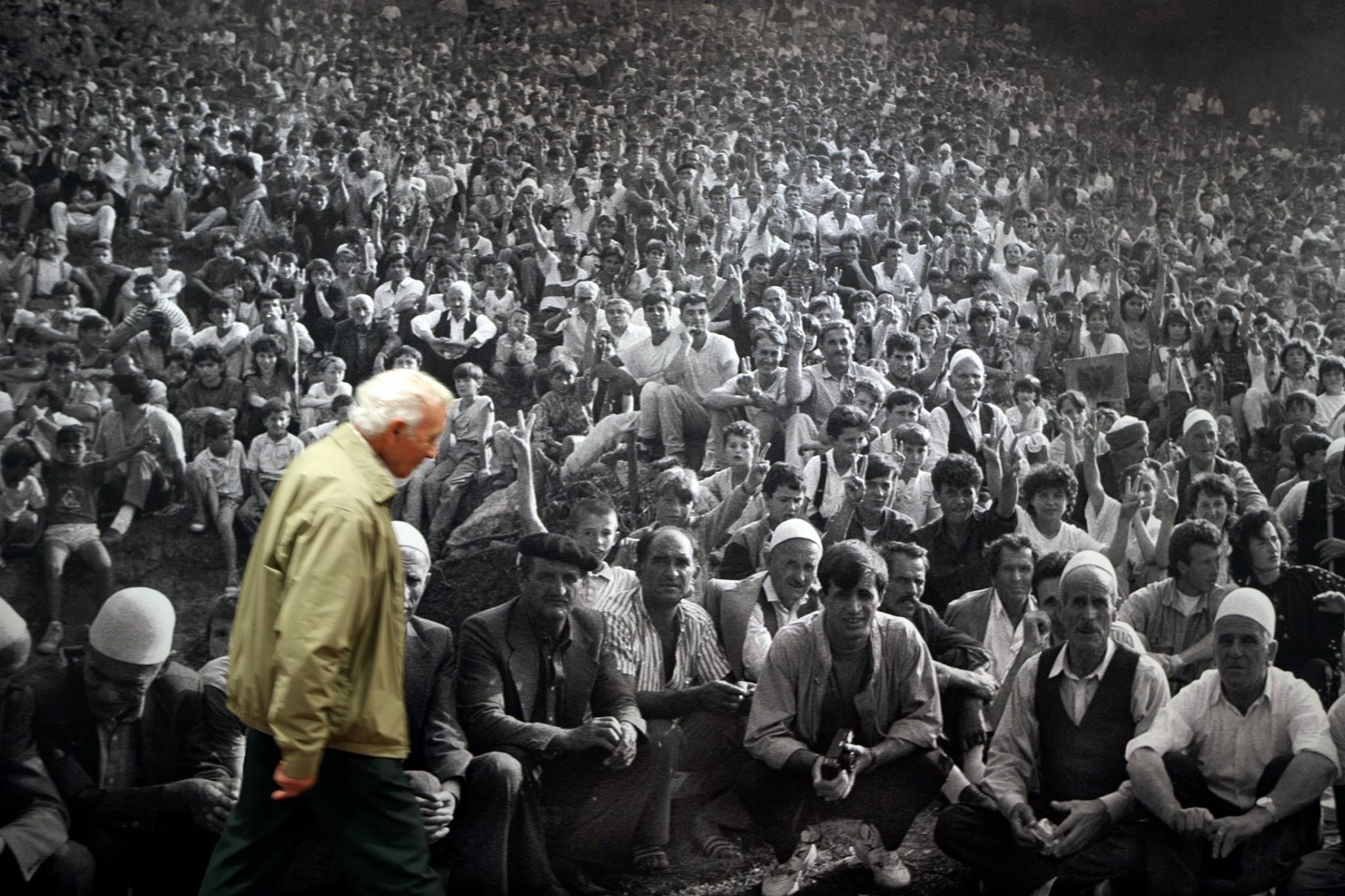

Meredith-Vula’s own role as witness transformed when, in 1990, she first learned of plans to reconcile blood feuds in the region where she was photographing haystacks. Temporarily setting aside her fascination for the rural sculptures, she turned her lens towards hundreds of people gathering at the behest of the Albanian folklorist and scholar Anton Çetta (1920-1995) to ceremoniously end revenge killings that had continued for centuries, paralyzing communities. Not directly implicated in the conflicts, but speaking fluent Albanian, she had a greater proximity to the situation than any foreign journalist. She also helped a BBC crew to realize the documentary, *Forgiving the Blood*.

Meredith-Vula’s unique perspective is clarified when considering that she often borrows a horse from a farmer and rides through the countryside after depicting it. She is not using the camera as something to hide behind, to keep a safe distance from the world, to remain cool and objective. I would venture that for Meredith-Vula’s, a camera is something like a horse, a comrade to travel with, to cooperate with in connecting to a place. Her work evidences an expanded community of people, animals, things.

Edi Hila, the eminent Albanian painter and beloved teacher of a younger generation of artists studying at The Art Academy of Tirana, has commented on the haystack photographs of his friend and fellow artist. They are, he notes: “Lala in dialogue with each haystack. It is what Lala has seen and what each haystack has said to her.” I share Hila’s sense of the sentient character of each individual pile of hay. He also notices in Meredith-Vula’s photography “a special sensitivity and an elusive intuition” that has “a dimension of abstraction, as much as it should without getting stuck.” If Meredith-Vula’s natural instinct comes from observing the particular genius of unsigned artworks in the landscape, the experience of seeing her photographs holds a related potential, particularly if we see these images a bit like the artist sees the haystacks – as partners in a conversation.

Such a conversation, a closer look, an intimacy with the photographs was key in the process of making this exhibition. On 4th May 1990 in Vranjevc, Prishtina, seeing people gathering around a house under construction with all the anticipation of making history, Lala Meredith-Vula stood witness, connected, pressed the shutter of her camera. Years later, the resulting photograph, which could be looked at for hours, yields a detail – a banner with the simple and sensible words, *Urtësi sot e mot* (Wisdom today and forever). These words begin to guide a broader vision of Meredith-Vula’s practice while also carrying the social and political vision of the people whom she depicted into their future, our present, and further. Such is the strange life of photographs. They capture an instant, yet their meanings continue to change with time. By including an historical image – Kel Marubi’s photograph of a crowd gathering for a Flag raising ceremony in the castle of Shkodër on March 19, 1914, which was recently exhibited as part of *Rroftë! (Long Live!) *curated by Blerta Hoçia – a conversation opens up between Meredith-Vula’s photographs and the rich archival holdings of the Marubi Museum. This crowd of 1914 finds echoes in several of the *Blood Memory* works from the early 1990s, and the question remains how they resonate in 2017. The conversation between photographs (and the public) continues …

It should be noted that this is a unique occasion when Lala Meredith-Vula’s two signature series – *Blood Memory and Haystacks* – are brought together to interact. Selections from these two bodies of work were recently shown in Athens and Kassel respectively, on the occasion of documenta 14. Documenta is an international art exhibition founded in Kassel in 1955, which now occurs every 5 years and seeks to present the most urgent developments in art and culture to a broad public (it is the most visited contemporary art exhibition in the world). The 14th edition, with the real and allegorical working title “Learning from Athens” was the first to occur in two cities on equal footing and this configuration was an opportunity to show different dimensions of each participating artist’s works in different locations. The Marubi Museum hosts a selection of works from the series *Haystacks*, shown in Kassel, and augments the selections from the *Blood Memory* series shown in Athens with never-before-exhibited images.

Meredith’s participation in documenta 14 as well as her exhibition in the Marubi Museum were made possible through the sage advice of Erzen Shkololli, who first introduced the photographer’s work to documenta 14’s artistic director, Adam Szymczyk, and curator, Pierre Bal-Blanc, along with several other key artistic positions from this region that ended up playing an important role in the exhibition in Athens and Kassel. Meredith-Vula’s works held great relevance for broader questions we continued to ask about ways in which to organize politically, ecologically and aesthetically and about how to imagine our way out of multiple, intersecting crises and conflicts – feuds that break up communities, alienation of people from the land, loss of memory. The gently guided gathering of neighbors and the unforced gathering of hay (even the lucky encounter between artist and curators), which cohere here, are evidence of wisdom that may grow with time.

Publication

Exhibition Credits

- Curated by

Monika Szewczyk

- Acknowledgements

American Bank of Investmens

Gjergj e Natalia Leqejza family

Erzen Shkololli