Ottoman clay smoking pipes from Rozafa Fortress in Shkodra [1]

One reads in the travel journal of Master Thomas Dallam that pipe smoking was practiced in the Levant as early as 1599.[2] It was introduced into Egypt between 1601 and 1603, and from there, it became common in Turkey by 1605. Then the custom of smoking spread rapidly through the Ottoman Empire, although use was strictly medicinal in the beginning. Very soon, smokers became addicted, causing Sultan Ahmet I to prohibit it already in 1612. Murat IV followed with a strict ban in 1633 and many people were executed as a result. In spite of the prohibition, several districts of Istanbul went up in flames in 1637 because of a burning pipe (one should bear in mind that houses during the Ottoman period were built mostly of wood and easily caught fire). The ban was lifted in 1646 because Mehmet IV’s government perceived an important source of income in pipe smoking. From then on, the use of tobacco and smoking spread rapidly, and as a consequence pipe production centers were opened in many towns. The town of Lüleburgaz got its name from the numerous pipe workshops situated there. Other workshops were situated in Istanbul, Sivas, Konya, Kayseri. Diyarbakır, Kütahya and Iznik.[3] By the middle of the eighteenth century, pipe smoking was in fashion for men and women regardless of age or social position. Another fashion that soon became popular, besides pipe smoking, was the smoking of the narghile, a water pipe, introduced already in the reign of Murat IV. A special tobacco called tumbak was smoked in these pipes.[4] Westernization led to cigarettes becoming fashionable by the twentieth century. Pipe smoking declined. The last pipe workshop,or atölye, which was owned by Ömer Usta, closed in 1928. Usta, or pipe makers, owned the workshops, in which they employed several workers, each with a different task in the pipe production process. Apprentices would prepare the clay and fashion the pipe in the mold. Then carvers would hollow the pipe and engravers and gilders did their tasks (see below). Pipe smoking disappeared while the fashion of smoking the narghile continued.

Smoking pipes that were in use across Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean, the so-called chibouks, are small, attractive items with miniature decoration, comprising a bowl with a separate stem. They are found at all archaeological sites with Ottoman occupation layers. Until recently, very few were found in clearly dated contexts. Pipes have been recovered as far as Russia, in tombs dated to the nineteenth century.[5]

Most smoking pipes are held in private collections and have rarely attracted the interest of archaeologists. Studies of Ottoman pipes in recent years include work on pipes from Athens and Corinth,[6] and from Saraçhane, Istanbul.[7] An important study on the pipes from Tophane, Istanbul was published by Erdinç Bakla.[8] This study dealt not only with pipes but with the entire pipe-smoking and coffee-drinking culture of the Ottoman period. Hüseyin Kocabaş analyzed pipes mainly from the Tophane workshops.[9] An extensive study on smoking and tobacco in the Serbian state in the nineteenth century was written by Boško Mijatović;[10] it includes aspects such as growing tobacco, taxation and monopolies. Studies on pipes found in the Balkan provinces of the Ottoman Empire are numerous, and deal mostly with museum collections.

Clay tobacco pipes and smoking as seen in the Marubi Archive

Ottoman rule in Albania began in 1479, after the fall of Shkodra, and continued despite on- going revolts and uprisings until 1912 when Albania declared its independence during the Balkan Wars. The “Turkish” habit of smoking pipes was as common in Ottoman Albania as it was in other provinces of the Ottoman Empire. One source is the Marubi Archive in Shkodra.

Pietro Marubbi was born in Piacenza, Italy, in 1832[11]. His alleged involvement in the murder of the Duke of Parma, forced him to leave his hometown and flee Italy for Corfu in Greece and ultimately Albania, where he was granted asylum in Shkodra. There, together with his wife Marietta, he settled down. He was called Pjetër, the Albanian form of his Italian name Pietro. He opened a photographic studio, “Marubbi,” in 1865 and took photos of local people, buildings, and panoramas. The two sons of Marubi’s gardener, Mati and Mikel (Kel) Kodheli, became his assistants. Only Kel and his son Gegë continued his legacy since Mati, unfortunately, passed away at a young age. The Marubis left an impressive archive that includes photos of landscapes, local aristocracy, people in ethnic costumes, and buildings — in short, anything worth photographing was captured on film by the cameras of the Marubis. The archive, one of the richest archives in the Balkans, houses more than 500,000 negatives on glass and film, many of which have been digitized.

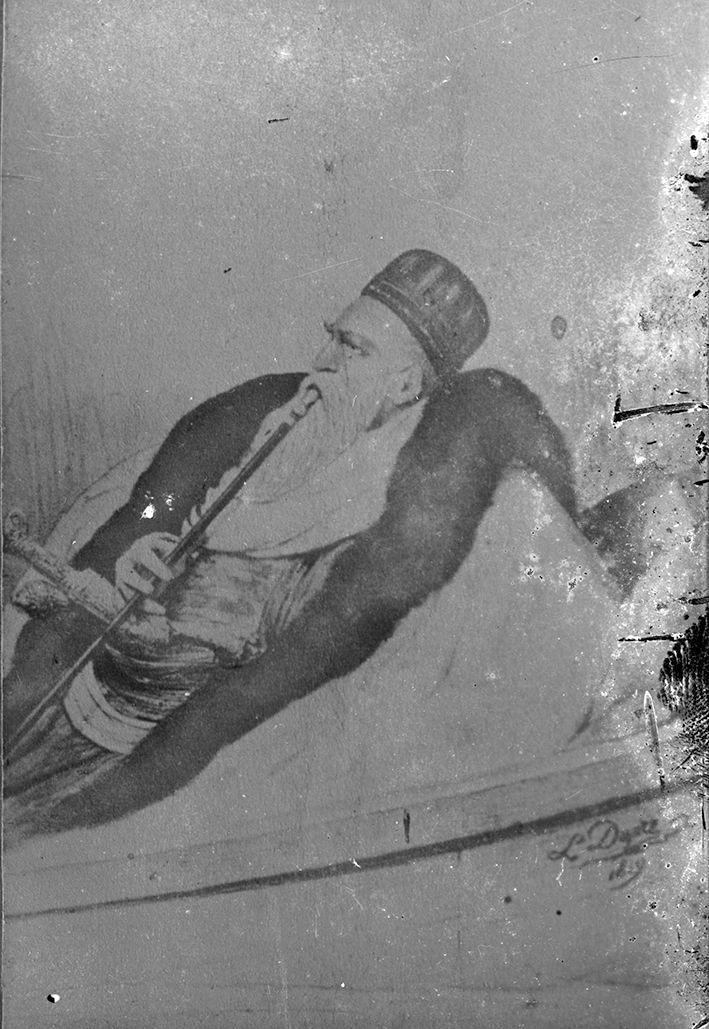

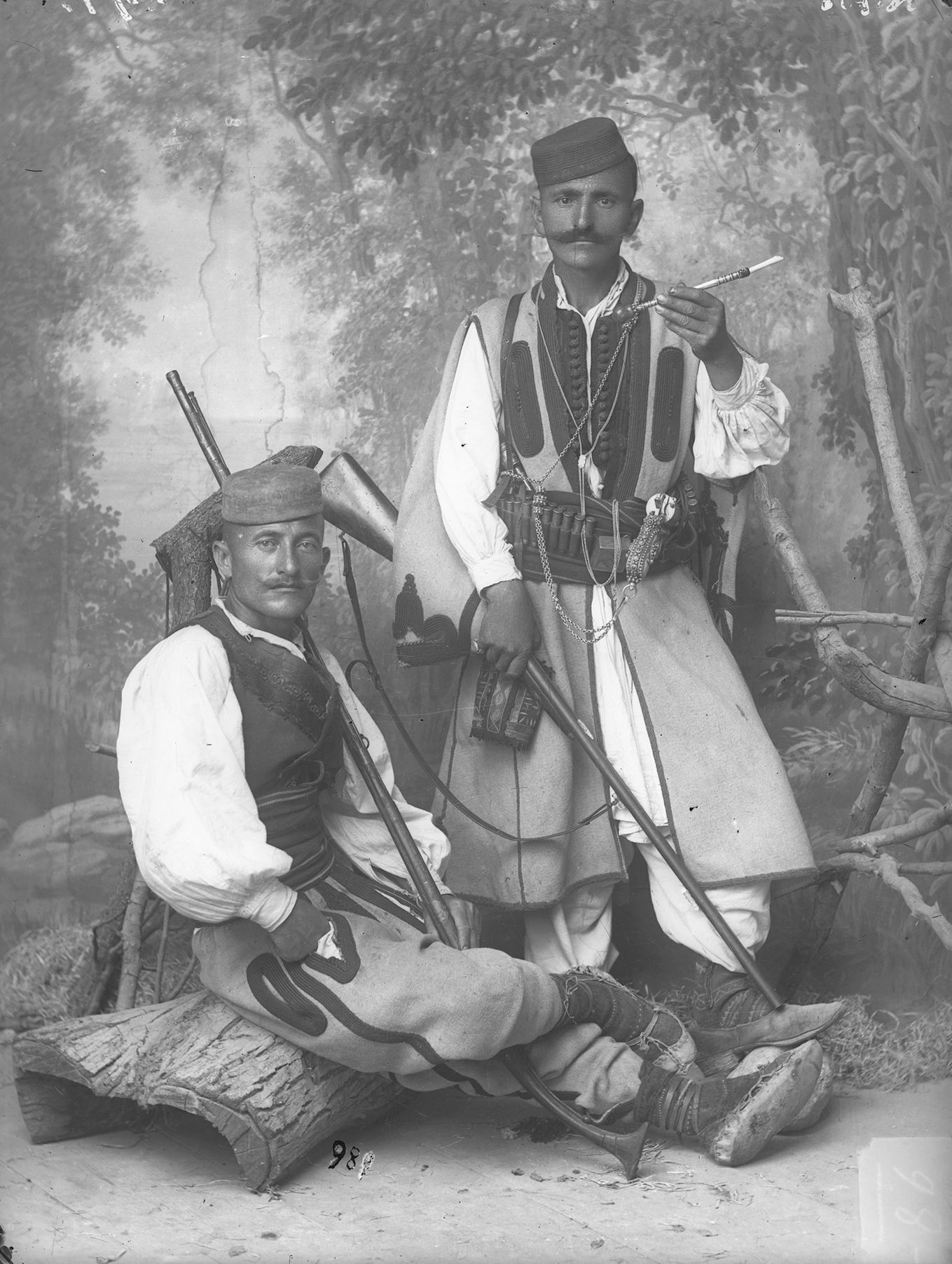

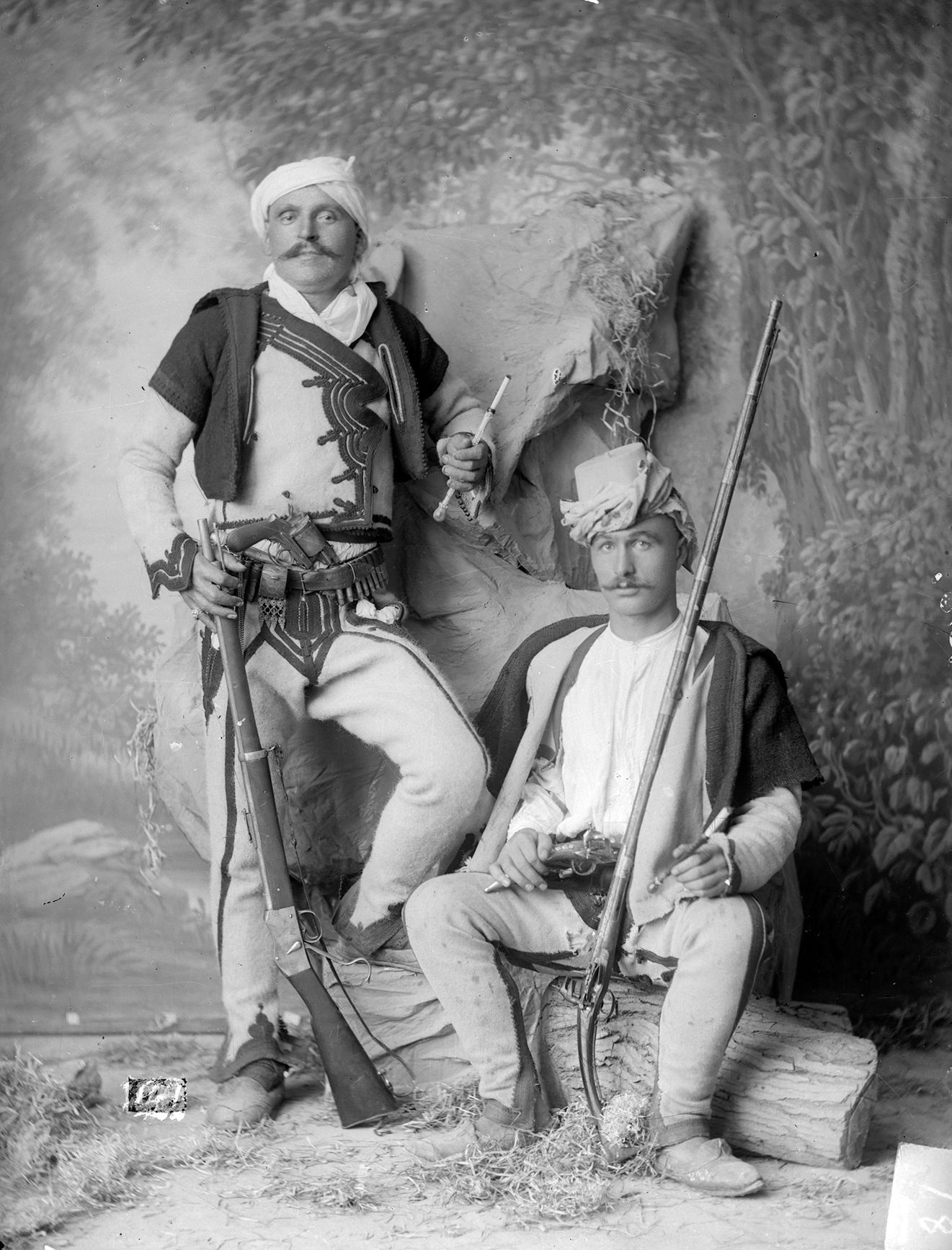

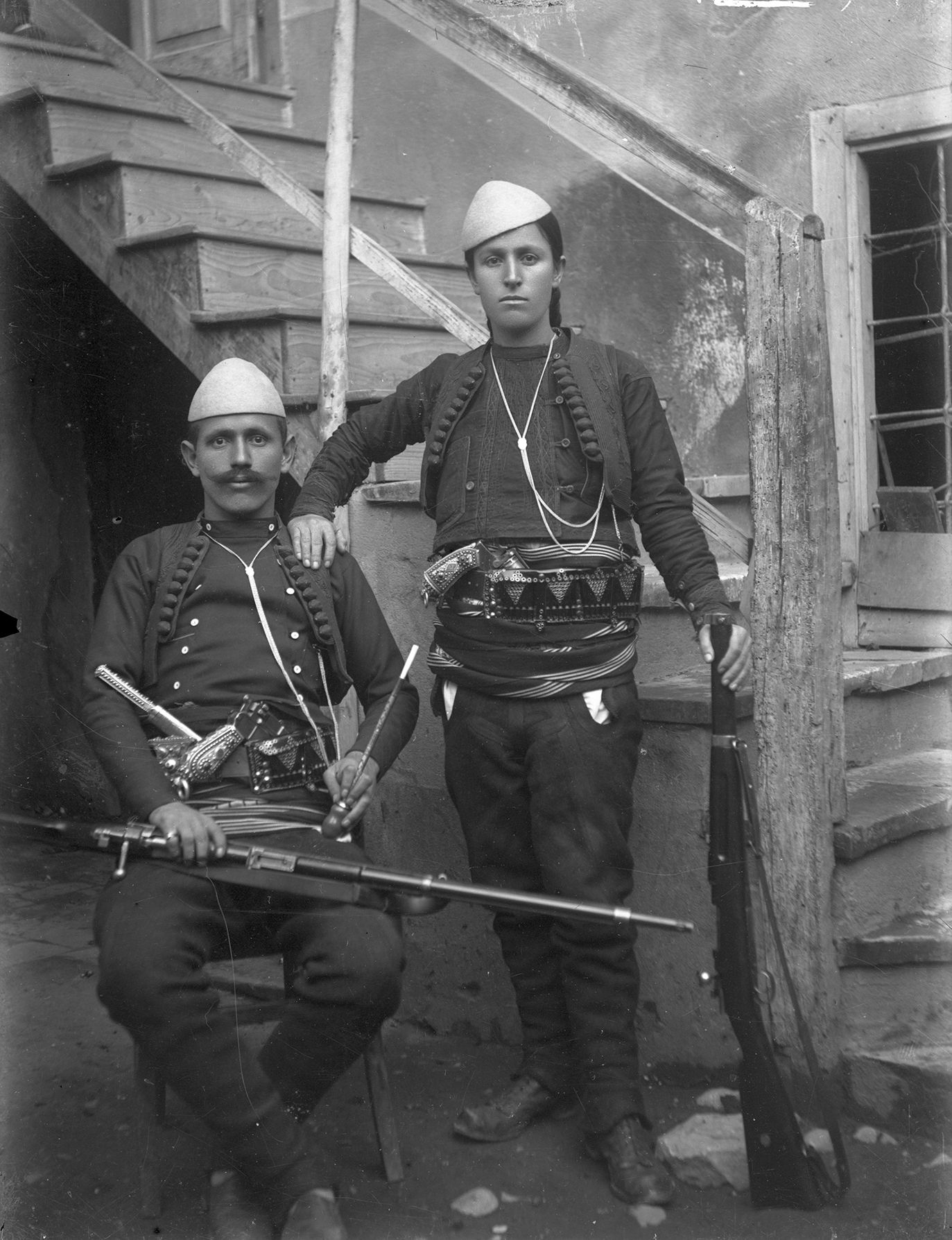

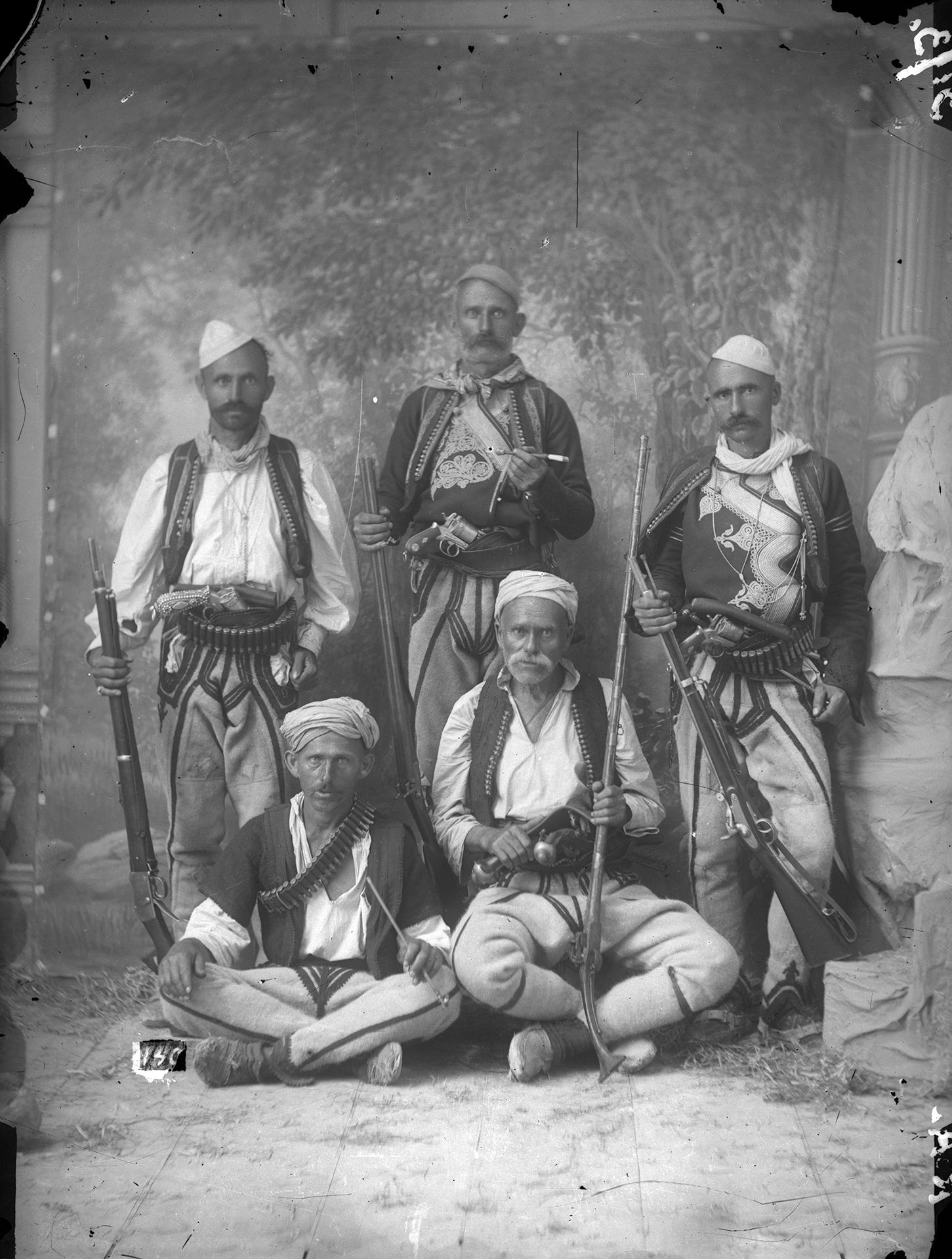

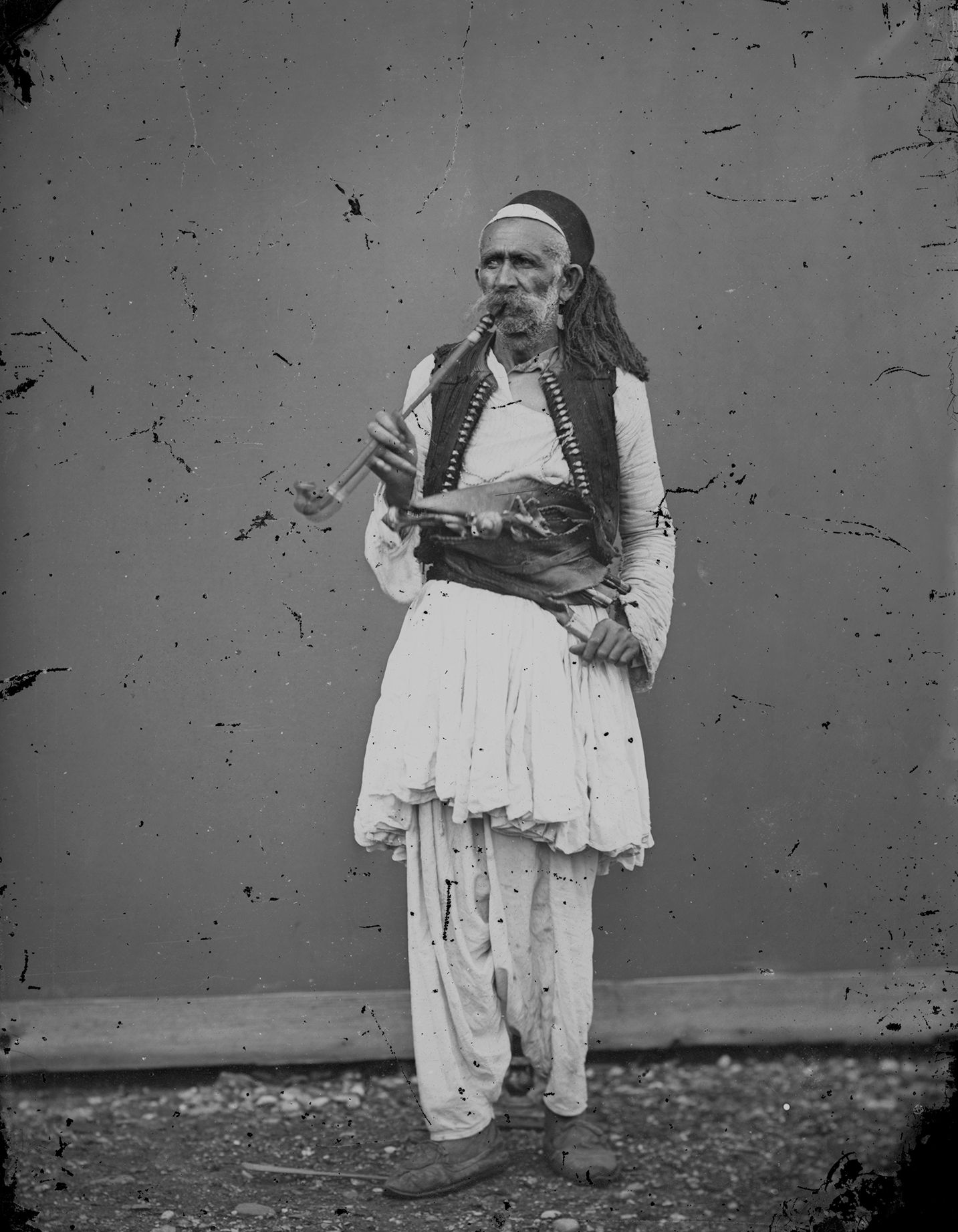

A few of the photos from the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century show chibouk smoking pipes [Figs. 1–2]. A man smoking a water pipe appears in one photo [Fig. 3]. Several photos dated to the beginning of the twentieth century depict men smoking cigarettes, but interestingly they use a short stem and a mouthpiece [Figs. 4–7].

Fig. 1. Man smoking a chibouk-type pipe (courtesy and copyright of the Marubi Archives, Shkodra) / Fig. 2. Ali Pasha of Tepelena reclining and smoking a chibouk-type pipe as indicated by the long stem and mouthpiece (courtesy and copyright of the Marubi Archives, Shkodra) / Fig. 3. Man smoking a narghile-water pipe (courtesy and copyright of the Marubi Archives, Shkodra) / Fig. 4. Local militia: one of the soldiers smokes a cigarette with a short stem and mouthpiece (courtesy and copyright of the Marubi Archives, Shkodra) / Fig. 5. Local militia: both soldiers hold cigarettes with a short stem and a mouthpiece (courtesy and copyright of the Marubi Archives, Shkodra) / Fig. 6. Two members of the Albanian resistance in Kosovo during the Balkan Wars: Azem Galica and his wife Shote. Azem is holding a cigarette with a short stem and a mouthpiece (courtesy and copyright of the Marubi Archives, Shkodra) / Fig. 7. Local militia: the soldier standing in the middle holds a cigarette with a short stem and a mouthpiece, the soldier on the left holds what seems to be a small pipe (courtesy and copyright of the Marubi Archives, Shkodra)

The research by Anna de Vincenz “Ottoman Clay Smoking Pipes from Rozafa Fortress in Shkodra” is part of the series “Scodra. From Antiquity to Modernity” published by the Center for Research on the Antiquity of Southeastern Europe, University of Warsaw (2020).

Dr. Anna de Vincenz is an Israel-based archaeologist and independent researcher. She has conducted extensive fieldwork in Italy, Germany, France and Israel and has been a pottery specialist in Israel and abroad on sites dated to the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Islamic, and Ottoman periods. Her current focus is on the material culture of the Ottoman Empire. She has published various reports and articles on ceramic and porcelain finds from Ottoman-period sites in Israel. Moreover, she has published articles about smoking pipes from Montenegro, Albania and Iraqi Kurdistan. Dr. de Vincenz received her Ph.D. at the Department of Near Eastern Languages, Civilizations and Archaeology of the Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples, Italy.

annasolari@gmail.com

https://aiar.academia.edu/AnnadeVincenz

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-3212-7205

References

[1] This is an excerpt of an article on the Ottoman smoking pipes found during archaeological excavations at Rozafa Fortress, Shkodra. A. de Vincenz 2020, “Ottoman Clay Smoking Pipes from Rozafa Fortress in Shkodra”, [in:] Scodra. From Antiquity to Modernity I: A Companion to the Study of Scodra, eds. P. Dyczek and S. Shpuza. Warsaw, pp. 245–277. Some of the information on the photographer Pietro Marubbi was corrected and updated from the PhD study of Dr. Luçjan Bedeni “Pietro Marubbi and the establishment of the first photography studio in Albania” (2021).

[2] J. T. Bent, Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant. I. The Diary of Master Thomas Dallam, 1599–1600. II. Extracts of the Diaries of Dr.John Covel, 1670–1679. With Some Account of the Levant Company of Turkey Merchants, London, p.49, note 1.

[3] E. Bakla, Tophane Lüleciliği: Osmanlı’ nın tasarımdaki yaratıcılığı ve yaşam keyfi [Tophane Creativity of the Ottomans in Design and Joy of Life], Istanbul, p. 363.

[4] Bakla, ibid. p. 362.

[5] M. Stančeva, “O proizvodnji keramičkih lula u Bugarskoj” [About the production of clay pipes in Bulgaria], Zbornik — Muzej primenjene umetnosti 19–20, pp. 129–137 (French summary).

[6] R. C. Robinson, “Clay tobacco pipes from the Kerameikos”, MDAIA 98, pp. 265–285. R. C. W. Robinson, “Tobacco pipes of Corinth and of the Athenian Agora”, Hesperia 54/2, pp. 149–203.

[7] J. W. Hayes, “Turkish clay pipes: A provisional typology”, [in:] The Archaeology of the Clay Pipe, vol. IV, ed. P. Davey (= BAR International Series 62), Oxford, pp. 3–10. J. W. Hayes, Excavations at Saraçhane in Istanbul II: The Pottery, Princeton, pp. 391–395.

[8] E. Bakla, Tophane Lüleciliği: Osmanlı’ nın tasarımdaki yaratıcılığıve yaşam keyfi [Tophane Creativity of the Ottomans in Design and Joy of Life], Istanbul.

[9] H. Kocabaş, “Tophane lüleciliği” [Tophane Pipe Making], Türk etnografya dergisi 5, pp. 12–13.

[10] B. Mijatović, Tobacco and the Serbian State in the 19th Century, Belgrade.

[11] New facts on the life and activity of Pietro Marubbi were taken from the PhD study by Dr. Luçjan Bedeni “Pietro Marubbi and the establishment of the first photography studio in Albania” (2021)