Cultivating Flowers and Loyal Subjects: A Case Study of the Işkodra Municipal Garden

Starting in the year 1870, a new type of public recreation space referred to as the “people’s garden” (millet bahçesi) or municipal garden (belediye bahçesi) took root in the Ottoman Empire’s cities and towns. These formally landscaped spaces were modeled after Haussmann-era Parisian promenades.[1] Some of the new Ottoman public gardens that opened in Istanbul in 1870 emerged from the new municipal reforms that were implemented in the 1850s.[2] The passage of the Province Reforms of 1864 and 1871 transformed provincial towns and cities, albeit at uneven rates of development, with priority given to port towns as hubs of economic activity and trade.

There is a direct connection between the spread of the new public gardens and the expansion of infrastructure. New transportation technologies, such as tramlines, steamships and the railway network, not only linked the different neighborhoods of large cities together, but also tied the Empire’s provinces more closely to one another.[3] Yet it is also worth exploring how the gardens’ establishment paralleled other forms of infrastructural development that became tools and symbols of effective political control. Under the centralizing policies of Sultan Abdülhamid II (r. 1876–1909), building state institutions in the provinces, such as schools or hospitals, also served as visible proof of the command of a centralizing Ottoman state. The new public gardens served a similar function for Abdülhamid II. They became symbols of how urban or provincial reform could benefit the local populace in the creation of public or semi-public space.

Dozens of new public gardens opened across the Ottoman Empire during Abdülhamid II’s rule.[4] They were often situated in town centers, next to government offices and military barracks that housed the Ottoman bureaucracy, enabling officials to monitor these provinces more closely. This article looks at the establishment of one such garden in the town of Işkodra (now Shkoder, Albania) in order to understand how its existence, appearance and upkeep may have dovetailed with strategies for imperial presence and control at a time of political crisis in the Balkans.

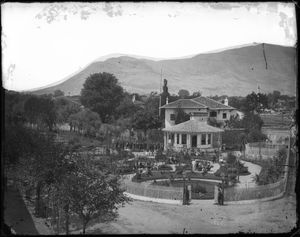

A photograph of the Işkodra garden appears in the Sultan’s extensive photography archive, stored in his library at the Yıldız Palace (figure 1).[5] This same photograph is reproduced years later in an issue of the Servet-i Fünûn journal, accompanying an article published on the Işkodra province, dating from 1895.[6] It bears the attribution Theodore (Th.) Vafiadis, who was not the creator of the image.[7] The photograph was actually taken by the Albanian photographer Pietro Marubbi, who immigrated to Işkodra from Italy in the 1850s and set up a photography studio that was operated for close to a century by his heirs.[8] Marubbi’s photograph of the garden is published again in 1914, in a book written by Wadham Peacock, the secretary to the British Consul in Işkodra.[9] Taken from a high vantage point – probably from the minaret or roof of an adjoining building – the image offers a lot of visual information. We see the garden’s layout and landscaping, and its staff, guards, and visitors. We also see the hills and mountains surrounding the town and the lake.

Figure 1: Pietro Marubbi, The people’s garden, Wet collodion, Glass 21×27 cm. Image courtesy: The Marubi National Museum of Photography.

Given Abdülhamid II’s love of gardens, and considering the care with which he had the grounds of his Yıldız Palace landscaped as an oasis, it is understandable why an impressive photograph of a picturesque garden would have appealed to his aesthetic proclivities. Yet the Işkodra garden may have held importance above and beyond its aesthetic appeal. A letter sent to the Sublime Porte by Işkodra’s mayor Hüsnü Hüseyin Bey, dated June 30, 1878, clearly outlines the garden’s significance.[10] In his letter, the mayor explains that he was granted permission by the Sublime Porte to improve the appearance of the town center. He enthusiastically reports that a garden, built in the “new style,” and its coffee house (kıraathane), now beautify a plot in the town center that had previously been an eyesore.[11] He explains that the municipality is responsible for the garden’s expenditures and revenue, and that he has entrusted a photograph of the garden to a soldier who will be bringing it to Istanbul. This is likely the photograph found in the Sultan’s library and taken by Pietro Marubbi.[12] In the photograph, the garden’s saplings appear very young, which suggests that it was newly landscaped. We also see a band playing in the garden, suggesting that the photo documents an event, perhaps the garden’s opening ceremony.[13]

Hüseyin Hüsnü’s letter waxes eloquently on the benefits of this public space. He explains that, prior to the establishment of the garden and coffee house, the residents of this town did not have a platform upon which to come together as citizens of one nation. If they needed to convene to discuss matters pertaining to their lands, the Christians would congregate in the churches and the Muslims would congregate in the mosques. They did not have a place they could gather in unison. He continues to explain that when the garden and its coffee house opened, the locals were not used to such vehicles of “progress and civilization,” and thereby regarded this site as a baneful establishment.[14] Now, however, little groups form within the garden, and Işkodrans come together in “brotherly love” to discuss important matters of the day.[15] Thanks to the garden and its ability to nurture feelings of national unity, he states, Işkodrans no longer view followers of the other religion with suspicion, but regard one another as “children of the same motherland”.[16]

Such an embellished description of the garden and its benefits suggests that the mayor wanted to underscore the garden’s political function for the Sublime Porte at this critical point in time. Işkodra was the capital of the Işkodra province (vilayet).[17] Even though it was situated on Lake Işkodra, it was not a port town, and was not linked to the rail network. It did not hold economic significance as a center of trade. Rather, its significance was political, and it gained further importance as a borderland that remained in Ottoman hands as separatist movements weakened Ottoman control in the Balkans. On July 1, 1876, about a month before Sultan Abdülhamid II took the throne, Serbia declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The region of Montenegro, forming Işkodra’s northern border, declared war the next day. The Bulgarians also demanded independence. As a stakeholder in the Balkans and supporter of Slavic independence movements, Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire in April 1877, which ended in a crushing Ottoman defeat. Ottoman peace negotiations with Russia culminated in the signing of the San Stefano Agreement on March 3, 1878, and the Berlin Treaty on July 13, 1878. Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria and Montenegro gained their independence and Bosnia-Herzegovina became an Austrian protectorate.

The vilayet of Işkodra now formed the Ottoman Empire’s westernmost frontier. Albanian nationalist sentiment awakened in response to the independence movements of neighboring Slavic states. Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece threatened to annex neighboring territories settled by Albanian speaking peoples.[18] Montenegrin border incursions posed the most immediate threat, triggering clashes just north of Işkodra. Mayor Hüseyin Hüsnü responded to these skirmishes by sending a protesting telegraph to the prince of Montenegro.[19] When Montenegro’s borders were redrawn after the Treaty of San Stefano and Montenegro annexed Albanian land, Albanians organized in opposition. On June 10, 1878, in the days leading up to the Congress of Berlin, they formed the Albanian League for the Defense of the Rights of the Albanian Nation.[20] The League first met in the town of Prizren, then attended the Berlin Congress.[21] The Albanians wanted to ensure that they would have a voice in Berlin during the negotiations that would determine the borders of their lands.

Hüseyin Hüsnü’s letter mentions the Prizren League’s meeting, and he also sends a photograph of its delegates to the Porte. The ethnic makeup of these delegates interestingly included both Catholic and Muslim Albanians, united by a common language rather than religion.[22] Hüseyin Hüsnü reveals that six hundred Işkodrans gathered in the public garden to raise funds to send their delegates from Işkodra to Prizren. Thanks to the generosity of the Sultan who enabled the building of this garden, he states, the residents of Işkodra can move toward progress together. He engages poetic metaphors, saying that the garden succeeds in seeding and “cultivating strong ideas for young generations,” and that it allows these ideas to flow from one source, “like guiding and directing water”.[23] He concludes by drawing a parallel between the garden and educational institutions, encouraging the Porte to establish state-run schools of mixed religion in his province, to further cultivate progress and unity.

It might seem odd that an Ottoman official charged with securing administrative control would be supporting Albanian nationalist sentiment. Hüseyin Hüsnü’s very tolerant outlook may have pointed to an earlier and more permissive government policy that predated the formation of the Albanian League. Riots and uprisings erupted regularly in Albania, especially in the mountain regions of Işkodra, which were inhabited by Mirdita Catholics who tended to resist centralized Ottoman rule.[24] Yet these uprisings were often localized, and none of them articulated political autonomy for the entire Albanian-speaking population. The formation of the Albanian League was the first step on the path to Albanian self-determination, gaining momentum over the successive years, and culminating in an attempt at armed revolution that was put down by force in 1881.[25] During the Congress of Berlin, the League articulated two demands: territorial unity, and greater political autonomy.[26] In 1878, its calls for territorial unity against the land claims of surrounding Baltic states aligned with the Ottoman Empire’s own political interests, even if the government resisted the League’s call for political autonomy. Admiring the sentiments of Albanian national unity and praising their ability to come together, Hüseyin Hüsnü may have wagered that Albanians would rely on the sovereignty of the sultan as a guarantee against territorial partition, and that they would prioritize this goal over demands for political independence.

Hüseyin Hüsnü draws a parallel between the state-run schools and public gardens, designating both as ideological tools to cultivate loyal and obedient imperial subjects. Historians of the Hamidian regime have discussed how the Sultan’s education policies attempted to counter the influence and propaganda of foreign states and ethnic minority groups. He orchestrated these attempts through the building of schools.[27] Italy, Austro-Hungary, and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, three powerful entities vying to exercise control in Albania, had already established schools in Işkodra.[28] Hüsnü Hüseyin was cognizant of their threat to the Empire’s administrative hold over these lands. Rather than let Albanian nationalist sentiments turn into an independence struggle, he seems to have believed that state schools could provide an education that nurtured feelings of belonging to the empire and loyalty to the Sultan.

According to the Servet-i Fünûn article, however, infrastructure was still lacking in Işkodra in 1895. In addition to giving an overview of the province and its capital, the article discusses the status of the region’s roads and education. It compares roads to veins: they are like “lifelines” that “enable civilization to spread” and “bring prosperity”.[29] It explains that although the province still does not have adequate roads, this is certain to be remedied under the current governor, Abdullah Paşa. It reports that the region’s educational institutions are also substandard, and hopes that this will be fixed by the Sultan, an “edifier” who has the ability to bring “enlightenment, awakening, and progress” to his Işkodran subjects.[30]

The article concludes with a discussion of the public garden, and reproduces Marubi’s photograph (figure 2). It explains that although the photograph shows the garden when it opened, it has since lost its charm. The trees surrounding its perimeter have grown into a thick grove, the flowerbeds have been ruined, and the guards at the entrance gate are no longer in attendance. It does not explain the reason behind the removal of the guards but, similar to Hüseyin Hüsnü’s letter, it upholds the earlier appearance of the garden and its tidy landscaping as a metaphor for how provincial reforms and infrastructural development serve a “civilizing” mission for the local populace.

Figure 2: “Işkodra’da Belediye Bahçesi, (Le jardin public de Scutari d’Albanie)” published in Servet-i Fünûn, No. 239 (27 Eylül 1311 [10 October 1895]).

This patronizing belief that the Albanians required the Ottoman government as an engine of civilization was, of course, motivated by the need to maintain state control over lands and peoples that agitated for autonomy. State-run schools may have led to greater professional opportunities for their graduates, but these educational institutions were also ideological tools to cultivate loyalty to the Ottoman state. The garden may have also been a public benefit, giving the Işkodrans a beautiful space for public life, but this was a carefully monitored space, with guards controlling the types of activities or conversations permissible therein. The ability to tame nature exemplified in the highly ordered appearance of this and other public gardens across the provinces under Abdülhamid II served as evidence of the effective implementation of provincial reforms. As symbols of reform, the gardens can also be viewed as attractive displays of soft power, showing how the Ottoman state kept these territories and their subjects in line – especially those populations prone to agitation.

Işkodra’s first public garden is no longer extant, and it is not clear when it was paved over, but it did have a life beyond Ottoman rule. It is documented in Peacock’s book, published two years after Albania gained its independence.[31] A public library is also said to have opened on this site in 1939, suggesting that it continued to serve an edifying function while Işkodra remained under the jurisdiction of the local population.[32]

References

[1] Baron Haussmann hired engineer Adolphe Alphand and horticulturalist and gardener Barillet-Deschamps to design Paris’s new public gardens in the mid nineteenth century. They included “English style” or paysagiste gardens, landscaped with winding footpaths, serpentine lakes, and artificial valleys and hills to give their constructed environments a more “natural” look. A. Alphand, Les Promenades de Paris (Paris: J. Rothschild, 1867–73).

[2] For discussions of the connections between urban reforms and the establishment of the new public gardens see Zeynep Çelik, Remaking Istanbul: The Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986), 69–70; Berin Gölönü, “From graveyards to the ‘people’s gardens’: The making of public leisure space in Istanbul,” Derya Özkan and Güldem Baykal Büyüksaraç, eds., Commoning the City: Empirical Perspectives on Urban Ecology, Economics and Ethics (Routledge: Abingdon and New York, 2020), 104–122; and Mehmet Kentel, “Assembling ‘cosmopolitan’ Pera: An Infrastructural History of Late Ottoman Istanbul” (PhD diss., University of Washington, 2018), 99–146.

[3] As an example, a new omnibus line (a horse-drawn tram on wheels) was laid down in the Kısıklı neighborhood of the Üsküdar district in Istanbul in 1870. BOA.HR.MKT 690/21 (15 R. 1287 [July 15, 1870]). This was a somewhat remote location, but soon after the establishment of the Kısıklı omnibus line, the Çamlıca (or Kısıklı) public garden opened on this route, making it accessible for residents from different neighborhoods around the city.

[4] Through Ottoman state documents, photographs and postcards, I found evidence of new public gardens opening in Adana, Ankara, Baghdad, Balıkesir, Beirut, Dedeağaç, Draç, Edirne, Erzurum, Filibe (Plovdiv), Giresun, Haifa, Halep (Aleppo), Jerusalem, Işkodra (Shkoder), Izmir, Izmit, Manisa, Mersin, Midilli (Mitilene, Lesvos), Mosul, Selanik (Thessaloniki), Siroz (Serres), Sivas, Şam (Damascus), Trablusşam (Tripoli, Lebanon), Trabzon, Üsküp (Skopje), Varna and Yanya (Janina) between the years 1876 and 1909.

[5] Istanbul University Central Library, Rare Works Collection (İÜMK), 90419/1.

[6] Servet-i Fünûn, No. 239 (27 Eylül 1311 [10 October 1895]).

[7] Republished photographs of this era are commonly attributed to a different photographer than the original creator of the image.

[8] The attribution of this photograph was confirmed in an email by Luçjan Bedeni, dated March 18, 2021. He is the director of the Marubi National Museum of Photography in Shkoder, which contains the Marubi studio archives. Marubi’s name is sometimes spelled Marubbi in archival documents. Roberto Mancini states that the original Italian name was Marrubbi but the spelling Marubi might reflect the Albanian pronunciation of his name. Robero Mancini, “Monumenta Historiae Patriae: Marubi’s Photographic Documentation (1858-1970) and the Birth of the Albanian Nation,” in Photo Archives and the Idea of Nation, eds. Costanza Caraffa and Tiziana Serena (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2015), 119–139.

[9] Wadham Peacock, Albania, The Foundling State of Europe (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1914).

[10] BOA.İ.DH 770/62738 (12 Haziran,1294 [June 30, 1878]).

[11] Ibid.

[12] This is the only photo of the Işkodra garden that I have encountered in any of the sources I consulted.

[13] According to the Marubi Studio archives, this image is dated 1875, although Hüseyin Hüsnü Bey’s letter indicates that the photo was taken closer to 1878.

[14] BOA.İ.DH 770/62738 (12 Haziran,1294 [June 30, 1878]).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Albanian speaking populations resided in four different Ottoman provinces: the vilayets of Işkodra, Kosovo, Manastır and Yanya.

[18] Stavro Skendi, The Albanian National Awakening, 1878-1912 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), 31–53.

[19] Vahit Cemil Urhan, “Ayastefanos ve Berlin Antlaşmaları Sürecinde Karadağ’ın Bagımsızlığını Kazanması,” Avrasya Etüdleri, 50:2 (2016): 235–258.

[20] Stavro Skendi, “Beginnings of Albanian Nationalist and Autonomous Trends: The Albanian League, 1878- 1881,” The American Slavic and East European Review, 12:2 (April 1953): 219–232.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Skendi (1967), 36–38.

[23] BOA.İ.DH 770/62738 (12 Haziran, 1294 [June 30, 1878]).

[24] For a discussion of Ottoman policies toward various Albanian ethnic populations, see Paolo Maggiolini, “Understanding Life in the Ottoman–Montenegrin Borderlands of Northern Albania during the Tanzimat Era: Catholic Mirdite Tribes, Missionaries and Ottoman Officials,” Middle Eastern Studies, 50:2 (2014), 208–232, DOI: 10.1080/00263206.2013.870891

[25] The Ottoman government disbanded the League and arrested its leaders after armed members occupied Prizren, Üsküp, and Priştine, and ousted Ottoman officials. Skendi (1953), 226–230.

[26] The League wanted to combine the four different provinces inhabited by Albanian speaking peoples into a unified Albania. Skendi (1953), 225–226.

[27] For a discussion of the expansion of state-run schools under Abdülhamid II, see Benjamin C. Fortna, The Imperial Classroom: Islam, the State and Education in the Late Ottoman Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). For a discussion of the Ottoman state’s competition with foreign missionary schools during these same years, see Selim Deringil, The Well-Protected Domains: Ideology and the Legitimation of Power in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1909 (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 93–111.

[28] Isa Blumi, Reinstating the Ottomans, alternative Balkan modernities, 1800-1912 (New York: Plagrave Macmillan, 2011), 151–174.

[29] Servet-i Fünûn, (1895), 70.

[30] Both Hüseyin Hüsnü’s letter and the Servet-i Fünûn article support observations made by Benjamin Fortna that Ottoman officials in the provinces embraced the prospect of state education as a “panacea” for a host of local ailments. Fortna (2002), 43–86.

[31] Although Peacock does not credit Marubbi in his book, he does credit “Vali Hüssein Paşa” for establishing the public garden. Peacock (1914), 63–64.

[32] The information about the public library comes from the Marubi National Museum of Photography, and was shared in email from Luçjan Bedeni dated June 2, 2021.

Berin Gölönü is an Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Studies at SUNY Buffalo. She is currently writing a book about the history of late-Ottoman public gardens established between 1870–1918. Her selected writings can be found on http://www.beringolonu.com/.